Writing memorable characters your readers won’t forget is difficult, and there are so many people out there telling you the best way to create them. But if you’re wondering how to create characters with strong personalities, there’s only one book you really need to read, because it has actual insights from psychologists.

The Science of Writing Characters by Kira-Anne Pelican is an excellent resource for writers, tackling the big problems we all face. There’s one chapter that I visit every time I’m creating characters for my next writing project, and in this post I go through my process.

Disclosure: If you use links to any books in this blog post, I may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops.

About The Science of Writing Characters

I attended a workshop facilitated by Kira-Anne Pelican in 2021, which is when I was introduced to her psychology-driven technique of assessing and creating characters with strong personalities. Immediately afterwards, I bought her book The Science of Writing Characters and I’ve used it every year since.

The book is described as “a comprehensive handbook to help writers create compelling and psychologically-credible characters that come to life on the page”, and it really is. The chapter I keep coming back to is chapter 2, dedicated to the “Big Five” dimensions of personality, which the author categorises as:

- extraversion

- agreeableness

- neuroticism

- conscientiousness

- openness to experience

The dimensions of personality are used in psychology, and in this book Kira-Anne takes concepts from psychology to create frameworks for writers to use. She references popular culture figures like Midge from The Marvellous Mrs. Maisel, Lisbeth Salander from The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and many more in reference to the dimensions of personality.

Author Kira-Anne Pelican is a writer, story consultant, researcher, and script editor who runs character workshops for writers across genres and media. Her knowledge comes from her background in psychology, which she uses to help writers create more compelling characters. You can read more about her work on her website.

The book also includes more sections – including on Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the Dark and Light Triads of personality, dialogue shaped by personality, the 15 evolutionary motivations, emotional arcs, and secondary characters – and a whole chapter on character workshops using all of the theories contained inside.

In this article, I’m going to focus on how I use the dimensions of personality to create strong, unforgettable characters with reference to the book. Hopefully I’ll inspire you to use the book yourself to build, develop, or strengthen your own characters.

How to use The Science of Writing Characters to create characters with strong personalities

While I won’t be sharing everything the book contains, I will explain how I use the chapter on dimensions of personality to build characters with strong personalities before I begin writing a story. In my experience, I primarily write fantasy and speculative fiction, but the depth of the book allows for a lot of different characters and situations.

How to use the 5 dimensions of personality

In chapter 2, the author introduces each of the dimensions one at a time. I’m going to give a quick overview of what to expect and then explain my step-by-step guide to using this chapter to build strong characters.

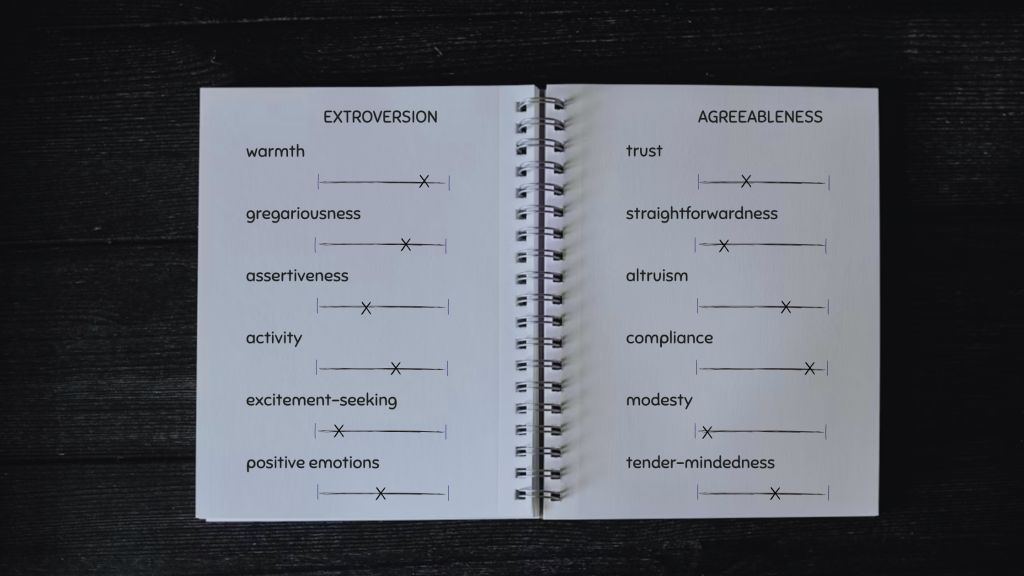

Each dimension of personality has six facets, which are traits associated with the dimension. With each facet, the author offers questions to help you decide where on the spectrum your character sits for each facet. Using the questions, you can use the spectrum of ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ to judge how strongly or weakly the facet appears in your character.

For example, let’s start with the first dimension, extroversion. The six facets of extroversion are warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement-seeking, and positive emotions.

Under assertiveness, Pelican writes:

Is your character generally assertive?

Or does your character often feel inferior to others?

By answering these questions, you can determine where your character sits on the spectrum of assertiveness to inferiority.

Let’s say I have a character who is an apprentice of a wizard. I might wonder whether they feel inferior to others because of their current station (as an apprentice) or whether they’re assertive in comparison to others in their position. You have a lot of wiggle room to interpret each facet in a way that works for your story and the world they’re in.

Another example could be a royal guard in a kingdom. Assuming they are the same rank as the other royal guards, asides from their captain, they might be one of the more assertive characters, feeling more confident and forceful, bossing the others around when things need to be done. Or they might feel imposter syndrome and be more of a follower, looking to others for directions.

When I create characters, I use either a two-page spread in an A4 notebook or one A5 page per dimension to go dimension by dimension. I write down the dimension and the six facets for each, with a slider to determine where my characters’ personalities sit.

Here’s a quick mock-up of how I work, using the example of the wizard’s apprentice:

Using the questions for each facet, I draw a quick line and then mark on the line where I think this character’s personality sits. For the apprentice, I think they’re generally extroverted, but they’re not keen on having an exciting life, they prefer what they’re used to: a quiet, scholarly environment. While they’re altruistic and care about others and their needs, they also don’t trust someone at face value and they have a tendency to come across as arrogant.

Another way to use this framework involves answering each question more deeply. You might write a paragraph per dimension, summing up the character’s personality and highlighting their strongest facets.

There are also other ways to use the dimensions laid out in the book. One of the author’s suggestions is to look at all thirty facets of dimension and then rate which facets your character scores most strongly.

Creating multiple protagonists for the same story

Having multiple protagonists makes it even more difficult to create strong characters who are distinct from each other. With every perspective switch, your readers will follow different people in the world, and if they’re too similar then the reader will get confused.

Consider: have you ever read a book where the two protagonists are so interchangeable that you had to go back a page to check which character you were following?

I use the dimensions of personality to make a deliberate effort to avoid this. After plotting the facets for one character, I then work on the next character’s facets, but with more of a pause before plotting each point. I can’t have two characters whose personality strengths and flaws are the same, so the second character’s plot points are deliberated for longer.

The biggest problem is the fifth dimension: openness to experience. Surely most protagonists have to be open to new experiences?

But if they have the same approach to experiences, that’s a concern. So I might make one character be prone to daydreaming and have a vivid imagination, but the other character then has to be either the opposite or just have one aspect (daydreaming or a vivid imagination). If the first character also loves trying new activities, the second character could then be the opposite or be much more rigid.

This shapes how your characters will respond to the same situation. My daydreamer who loves new activities might have always thought about trying archery, so when they are forced into archery training they take to it well… but they struggle to concentrate on the skill aspect of archery because they’ve dreamed of being a natural at it. Meanwhile, my imaginative character dreads learning something new because they think they’ll struggle, but because they have more focus they work on the skill much more quickly.

I might have the same thoughts if I was writing a scene without planning their dimensions of personality, but the biggest advantage of this exercise is consistency. If I haven’t planned for the daydreamer to love new activities, I might have another scene where they randomly act like trying new things is the worst thing ever.

There are many ways to adapt this framework for yourself, but try going through the chapter as it’s laid out first.

Tips for creating unforgettable characters

One of the best quotes in the book concerns making memorable characters:

Remember that characters who score moderately across all five dimensions will typically be less memorable. So in order to create a memorable central character, make sure that they rate towards the extremes of at least one or two of these dimensions.

Unforgettable characters are an author’s biggest asset when making an impression on their readers. Based on my experience of using the book, here are my own top tips for making characters that stand out, whether they’re loved or hated:

- You don’t need to make characters who are loved to be memorable. Some of the most memorable characters are hateful, abrasive, or selfish. Think of all of the slimy villains who manipulate the heroes of their story, and all of the companions who betray the protagonists.

- Think about how you want your characters to be described by readers. What two adjectives do you want to come before their name? Your job is to make these adjectives obvious and integral to that character’s actions, dialogue, and part in the plot.

- Characters that defy stereotypes, such an anxious extrovert, will be more memorable but not necessarily more understood. The key with these characters is to make sure they feel realistic and act consistent.

- You can have characters who are hypocrites, but try to think about how they reason with themselves. Why is an altruist also cynical and distrustful of people? Are they really an altruist or do they just want to be seen as altruistic?

- It’s easy to fall into an unproductive spiral of doing too much character development, so figure out a system that works for you. Some people prefer asking their characters deep questions like an interview or hot seat or writing a short biography of their life before the beginning of the story.

Buy or wishlist the book

I highly recommend buying or borrowing The Science of Writing Characters for any writer, especially if you have multiple protagonists. It’s a fantastic resource for anyone struggling to create strong characters or wanting to try new ways of building characters. If you’ve been convinced, visit any of the links below to add to your TBR list or order from bookshop.org.

My link to bookshop.org goes to the UK site and is an affiliate link, so if you do buy the book I may earn commission on the sale at no additional cost to you.

Otherwise, try to support your local library or independent bookshops. The book is also available on Amazon and other large retailers.